How Can Domain-Driven Design and Hexagonal Architecture Improve Data Product Development in Practice?

When building business intelligence dashboards, AI models, or other data products, it is essential to understand the data being consumed and to have reliable access to information describing it. When unexpected results arise during analysis, practitioners must be able to identify their origins and underlying causes.

Data products often depend on other data products, forming a data supply chain [1]. Confidence in this chain is essential for delivering business value. Downstream consumers need to understand the characteristics of their inputs, and consistency across the chain is critical for success. This transparency mirrors physical goods in industry: consumers expect information about characteristics, production processes, and provenance. In regulated contexts, such as those involving Personally Identifiable Information, missing information may even render a data product unusable.

Just as physical goods can be raw materials, semi-finished, or fully processed, data products can be exposed at varying levels of transformation depending on the need. Each level addresses different consumers and implies different expectations for quality, documentation, and guarantees.

This article demonstrates how improved data products can be designed by applying software development techniques, focusing on business concept modeling, governance, and implementation in code.

A code repository accompanies this article: https://github.com/RolandMacheboeuf/data-product-with-ddd-and-hexagonal-architecture-demo

Data mesh and Domain-Driven Design

The data mesh paradigm addresses the challenge of scaling data initiatives by promoting domain-oriented ownership. In this model, teams closest to a particular business domain are responsible for the creation, maintenance, and exposure of data products. Each data product is treated as a discrete asset with clearly identified consumers, versioning, and documentation. This decentralization enables organizations to align data production with domain knowledge, while supporting autonomy and scalability across multiple domains.

However, decentralization alone is insufficient to guarantee trust and interoperability across the data ecosystem. Data governance provides a unifying framework that establishes policies, standards, and best practices to guide data teams in the creation and operation of data products. Core governance elements include data quality metrics, schema definitions, and contractual specifications for each data product. Data contracts, in particular, formalize key information for data consumers, including data schemas, field descriptions, access methods, and quality metrics. When integrated into the development process, these contracts act as recipes, guiding the creation of data products and ensuring that quality and consistency are maintained throughout the lifecycle.

Integrating governance into the development process is essential. Data contracts are most effective when defined before or during the creation of a data product, rather than retrospectively. By storing data contracts in code repositories, teams can synchronize updates to contracts with changes in implementation, review them during code reviews, and export them in controlled formats during CI/CD pipelines. This approach embeds governance directly into the production workflow, allowing for automated quality validation and documentation that is always up to date [2].

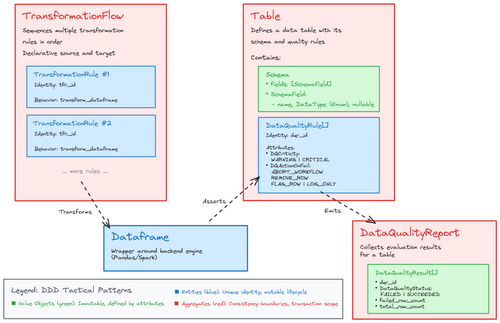

Data Governance as a specific domain

The creation of a data product can be summarized as a structured process: data is ingested from source systems, processed through transformations, and exposed to consumers along with associated quality metrics. Within this workflow, the Dataframe serves as an abstraction of tabular data, while Tables represent validated, structured outputs governed by quality rules. Transformation flows define the sequence of operations applied to a Dataframe, and compatibility checks ensure that outputs meet the contractual requirements before writing to persistent storage. Data quality evaluations can occur both during processing and post-write, enabling automated validation and alerting for non-compliant data.

Understanding the data consumer journey is equally important. Consumers typically explore available data products through an enterprise catalog, review the metadata and contractual information, obtain access, and integrate the data into their applications or analyses. Governance ensures that the consumer experience is consistent, reliable, controlled and aligned with expectations, regardless of which team produces the data.

Given the complexity and variability of business domains, premature technical solutions often result in misalignment or failure. Domain-Driven Design (DDD) provides a systematic approach to model the real-world business domain accurately. Central to DDD is the concept of ubiquitous language, a shared vocabulary used consistently across technical and business teams. This language informs naming conventions, documentation, and implementation artifacts, reducing misunderstandings and ensuring alignment between code and business intent. Collaborative workshops such as event-storming facilitate this modeling by mapping domain events, workflows, and bounded contexts, producing a visual representation of the full data flow and governance processes. Here is a reference card and a cheatsheet that can help you : Octo DDD reference card (French)[3] and Event Storming Cheatsheet [4].

Using DDD techniques to model the data governance and the data product life cycle seem like a good idea.

To clarify a bit, the full model of data product life cycle won’t be included in your code responsible for producing a single data product but having the bigger picture in mind while developing will definitely help to understand how this particular data product development is included in the general process. As a data team producing data products, you have some responsibility regarding the data governance processes.

The formalization of domain knowledge within the codebase strengthens the connection between governance principles and implementation. DDD provides a pattern to make alignment between business concepts and technical implementation. In a nutshell, DDD is targeting how to structure and organize your code in an epistemological way whereas Data Mesh is dealing with more global organizational aspects.

Concepts such as data quality status, criticality, evaluation results, and actions on failure can be represented as domain objects, value objects, or configuration artifacts. Storing these definitions alongside code, for instance in a domain_vocabulary.yaml file, provides a linguistic bridge between developers and business teams while enabling automation, validation, and documentation within the development workflow. This approach ensures that governance is not an afterthought but a foundational element of the data product lifecycle. The code should use those terminologies as much as possible to avoid understanding gaps. It can be combined with tools inside your IDE that will give you hints on the domain object definitions (you can look at Contextive [5]). I didn’t follow any standard format for this example.

domains:

- name: "data_governance"

description: "Universal domain covering data quality, schema management, and architectural patterns. These concepts apply across all business domains."

ddd_patterns:

value_objects:

- name: DataQualityStatus

description: "Status of a data quality evaluation (FAILED, SUCCEEDED)."

purpose: "Represents the outcome of DQ rule execution."

values: "FAILED or PASSED"

- name: DQCriticity

description: "Severity level of a data quality rule (WARNING, CRITICAL)."

purpose: "Determines the impact level when DQ rules fail."

values: ["WARNING", "CRITICAL"]

- name: DataQualityResult

description: "Result of a single data quality rule evaluation."

purpose: "Encapsulates the outcome of evaluating one DQ rule against a dataset."

attributes:

- dqr_id: "ID of the evaluated rule"

- status: "DataQualityStatus"

- failed_row_count: "Number of rows that failed the rule"

- total_row_count: "Total number of rows evaluated"

- error_message: "Optional description of the failure"

...

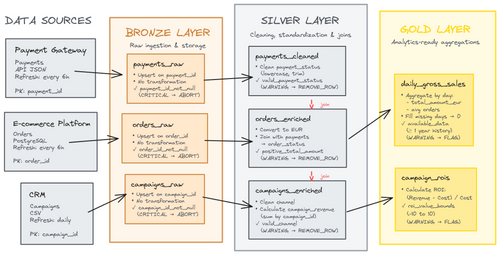

A Retail Data Product Domain

To illustrate the concepts discussed, we consider a simplified example of a retail data product focused on products, consumers, and marketing campaigns. The business objective is to analyze marketing campaigns from multiple sources and produce a unified view to evaluate campaign performance, for instance by computing the Return on Investment (ROI) for each campaign. The data product primarily serves the analytics team, but it can also provide value for downstream data products, dashboards, or ad hoc analyses.

The data product will be hosted on a data platform, providing the infrastructure necessary to operate data products consistently, securely, and at scale. The development of the data product begins with defining assertions and constraints for the data, specifying required transformations, and establishing availability and refresh requirements. Following initial stakeholder interviews, the sources of data were identified as follows:

- Payment data accessible via an API in JSON format.

- Orders from the e-commerce platform, stored in a PostgreSQL database.

- Customer relationship management (CRM) data, temporarily extracted as CSV files from an on-premises system and uploaded to secure cloud storage until integration via an iPaaS solution is established.

After ingestion, all data will be standardized in Delta table format, and processing will be conducted in Apache Spark due to the high volume of daily orders. To ensure systematic improvement of data quality and usability, the Medallion Architecture has been adopted. This multi-layered pattern organizes data into Bronze, Silver, and Gold layers, representing incremental improvements in quality, structure, and business value as data progresses through the platform.

For example, to compute campaign ROI, it is necessary to merge orders, payments, and campaign tables. Some orders lack a direct status field; therefore, payment status is used as a proxy to include only successful transactions. Data quality is enforced at multiple stages: invalid payment statuses are filtered and logged, and workflows are aborted if critical primary keys are missing, preventing corrupted data from entering the system.

The governance framework and domain vocabulary for the retail data domain are formalized in the code repository. The vocabulary defines key concepts, validation strategies, transformation rules, and table structures, providing a bridge between technical implementation and business understanding. An excerpt illustrating the Bronze layer of the Medallion Architecture is shown below:

domains:

- name: "retail_data_domain"

description: "Business domain for e-commerce retail operations, organized using medallion architecture."

business_concepts:

orders:

description: "Raw data ingestion with minimal transformation, critical validation only."

transformation_rules:

- name: RawDataIngestionRule

description: "Minimal transformation for raw data ingestion."

transformation_type: "ingestion"

purpose: "Preserve raw data structure with basic type conversion."

data_quality_rules:

- name: OrderIdNotNullRule

description: "Validates that order_id is never null in raw order data."

criticity: "CRITICAL"

action_on_fail: "ABORT_WORKFLOW"

business_rationale: "Order ID is the primary key for all downstream processing."

...

Now we will explicit all data quality rules and transformation steps for all levels in a data contract file. It will hold all of our business understanding and can be used both for build and for downstream consumers. The data contract can be then processed in your deployment pipeline to export relevant information into your organization documentation tools (data market place or data governance). In this way of working the data contract is set up to date as each new rule is built to ensure that it holds the most up to date information. Here is an extract of a first data contract we could get (non-standard format):

data_product:

name: "sales_analytics"

domain: "retail"

owner: "data.team@shoply.com"

version: "1.0.0"

description: "Data product describing consolidated e-commerce sales (orders, payments, campaigns)."

sources:

- name: "orders"

system: "E-commerce platform"

format: "PostgreSQL"

refresh_rate: "every 6 hours"

contract:

schema:

order_id: string

order_date: date

...

primary_key:

- order_id

foreign_keys:

- customer_id

- campaign_id

- name: "payments"

...

- name: "campaigns"

...

transformations:

bronze:

description: "Raw ingestion and storage of source data in the data lake."

tables:

- name: "orders_raw"

rules:

- "Upsert on order_id since last execution."

- "No modification: types specified in the contract are preserved."

quality_rules:

- name: "order_id_not_null"

description: "Each order must have a unique non-null identifier."

level: "critical"

action_on_fail: "abort_workflow"

depends_on:

- "sources.orders"

...

silver: ...

gold: ...

output:

tables:

- name: "sales_gold_daily"

description: "Daily aggregated view of consolidated sales."

refresh_rate: "daily"

columns:

- date: date

- total_sales: double

- avg_order_value: double

- name: "campaign_rois"

description: "Analytical table by marketing campaign, calculating profitability (ROI)."

refresh_rate: "daily"

columns:

- campaign_id: string

- channel: string

- revenue: double

- campaign_cost: double

- roi: double

So we have now a detailed file documenting everything needed to build the data product.

From documentation to code

The principles discussed so far can now be translated into code. The emphasis should be on why and what we are building, rather than the specific implementation. Organizing the workflow and understanding the objectives naturally guides code architecture; conversely, even well-structured code cannot compensate for a disorganized project.

This approach is framework-agnostic. Here, Python is used for its flexibility, allowing explicit control over domain logic, transformation rules, and governance enforcement. This flexibility comes with greater responsibility for the data engineer to structure the code and enforce constraints consistently.

This section serves as introduction to the code repository: https://github.com/RolandMacheboeuf/data-product-with-ddd-and-hexagonal-architecture-demo

A reusable domain and governance framework

The foundation of the implementation is a data governance domain, which defines core concepts that can be reused across multiple data products. These concepts include tables, data quality rules, and transformation rules and flows. Together, they form a shared vocabulary and a consistent execution model.

At this level, the framework defines what a table is, how data quality is evaluated, and how transformations are expressed, without binding these concepts to a specific engine. For example, a table encapsulates its schema and the data quality rules that must hold, while data quality rules and transformation rules define clear contracts that concrete implementations must respect.

The purpose of this layer is not to encode business logic directly, but to provide stable abstractions on top of which data products can be built.

You can find the data_governance domain implementation here: retail_data_product/domain/data_governance.

Defining a data product using the framework

A concrete data product is created by specializing these abstractions. Tables, data quality rules, and transformation rules are implemented as classes that conform to the framework’s contracts. Through inheritance and polymorphism, shared behavior is reused and enforced consistently. For instance, a table can evaluate its data quality rules without knowing their concrete implementations, as long as they respect the expected interface. You can find this section in code here retail_data_product/domain/retail.

This design isolates business logic in explicit domain objects. As a result, table definitions, data quality expectations, and transformation intent can be read almost declaratively and tested precisely in isolation.

By structuring data products around domain concepts rather than scripts, the intent of the system becomes explicit. Data governance is no longer an external concern but an integral part of the model. Changes to business rules, quality requirements, or transformation logic are localized, reviewable, and testable. The execution engine may change, but the domain model remains stable, providing a durable foundation for data products as they evolve.

Example: enriching marketing campaigns

Consider the campaigns_enriched table. Its definition expresses, in domain terms, the structure of the data and the expectations associated with it: standardized channel names, computed revenue, and a well-defined primary key. A data quality rule such as ValidChannelRule does more than observe the data. It encodes a business decision by specifying how invalid values should be handled, in this case by removing rows that do not comply with accepted channels.

Transformation logic is modeled separately. Atomic transformation rules describe unitary business operations, such as cleaning channel names or calculating revenue per campaign. All the business logic can be regrouped in this section of code and tested properly without impacting the other code sections. I have already seen the case where a complex business decision tree was modelized to construct an artificial primary key. Having this section isolated helped tremendously to detect edge cases and ensure that our artificial primary key definition was correct with unit testing. The complex business logic did not clutter the data transformation flow with overhead, keeping it easy to read and to follow.

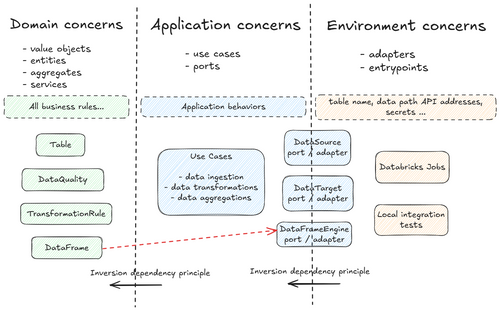

A hexagonal architecture to orchestrate the domain objects

So far, the discussion has focused exclusively on domain concerns. While we have defined rich domain objects and governance rules, we have not yet addressed how these elements are executed within concrete data flows. This requires introducing the application and infrastructure layers, and clarifying where program execution begins.

To structure this interaction, a hexagonal architecture is adopted. The core principle of this design is the strict separation between business logic and infrastructure concerns such as databases, processing frameworks, or external APIs. Business logic must remain independent of technical choices so that changes in infrastructure do not propagate into domain code.

This separation is achieved through ports, which define the capabilities required by the domain, and adapters, which provide concrete implementations of those capabilities. Domain and application code depend only on port interfaces, not on their implementations. As a result, the same business logic can operate with different infrastructures without modification.

Business logic is organized into use cases, which act as application-level orchestrators. In a data context, these use cases typically correspond to ETL tasks and are responsible for coordinating domain objects such as tables, data quality rules, and transformation flows.

Finally, primary adapters (or entry points) connect the application to its execution environment. They instantiate the appropriate adapters and trigger the relevant use cases. This layer defines where control enters the system, while preserving the isolation of the domain from infrastructural concerns.

Even if it does not represent a hexagon, here is a diagram that tries to summarize this in our case.

I introduce a special entity called DataFrame, which slightly breaks the purity of the domain layer by introducing execution concerns. This compromise is intentional: in data engineering, datasets are often too large to be loaded into memory and must be processed in a distributed way.

In big data systems, application code is executed by a driver node, whose role is to plan and orchestrate distributed computations across a cluster. For a computation to scale, each operation must be expressed in terms of the underlying data engine (for example Spark). If an operation is evaluated locally, the driver executes it in memory, bypassing the cluster entirely, which makes large-scale processing impossible.

From a design standpoint, this means domain logic must avoid constructs that implicitly force in-memory evaluation. While an alternative approach could rely heavily on UDFs and push all execution concerns to the application layer, this is not the path taken here.

Instead, the DataFrame acts as a bridge between the domain and the execution environment. The data itself never lives inside the domain or the driver; it remains in the distributed engine and in the external environment. The DataFrame preserves the domain vocabulary while delegating actual computation to the cluster, ensuring scalability.

To keep the domain independent from any specific framework, a DataFrameEngine port is introduced. This adds some boilerplate—each operation must be declared through the port—but it brings important benefits: the domain and application layers remain framework-agnostic, engines can be swapped (for example, Spark vs. Pandas) without changing any code on the business logic, and tests can run on lightweight in-memory engines. If engine stability is guaranteed, this abstraction can be simplified, but it provides valuable flexibility and long-term maintainability. This design choice is highly influenced by the context in which I evolved as a data engineer where I had the need to change between Spark or Pandas execution depending on the data volume. Indeed, for small datasets Spark is really slow because of the driver/node overhead. In general cases the recommendation would be to keep a single dataframe framework and use it directly inside the domain layers to make your transformations or data checks.

Implementing our example with DDD and hexagonal architecture

The following sections illustrate how the concepts we discussed are applied in code. The focus here is on structure and orchestration rather than implementation details that you can find by reading the code repository.

Data source and target

We define abstract DataSource and DataTarget ports to decouple domain logic from environment specifics. This allows testing transformations in memory while remaining agnostic to real storage (SQL, CSV, Delta, API). Adapters implement these ports for concrete sources/targets.

I am using very generic ports and adapters here but you want to use more specific ones and focus on what the application code is expecting, for instance RawCampaignSource for the Campaign ingestion task. Using more specific ports may help you introduce very specific behaviors. For instance if your ingestion is based on files, you can more easily add a specific rejection behavior defined by the application layer. Regrouping the ingestion of data from API, SQL tables or files under the same port may be a wrong design choice in some cases.

Use case orchestration

Data workflow tasks are implemented as use cases. A base class defines the common template (fetch, transform, validate, save), while subclasses implement the specifics using a template design pattern. This approach lets us define a common workflow in a base class and delegate the implementation of particular steps to subclasses, ensuring consistency and minimal code duplication while keeping flexibility. You can find the template use case here: retail_data_product/application/use_cases/base_etl_use_case.py.

Entrypoints / Primary adapters

Primary adapters connect the application to its environment. They instantiate sources, targets, and use cases, acting as the program’s starting point. Following the flow from the entrypoint clarifies each component’s role. If you are working with Databricks, the primary adapters would exactly be the task notebooks.

Example: EnrichCampaigns

This use case imports campaigns and orders, applies transformation flows (e.g., cleaning channels, calculating revenue), validates data quality, and writes to the target. All infrastructure details are hidden behind ports/adapters.

# Fetch data, apply transformation, validate, write to target

EnrichCampaigns(

campaigns_source=InMemoryDataSource(data=campaigns_data),

orders_source=InMemoryDataSource(data=orders_data),

campaigns_enriched_target=InMemoryDataTarget(data=[]),

dataframe_engine=PandasDataFrameEngine

).execute()

Wrap-up

The example repository demonstrates a reusable, testable architecture with clear separation of concerns. It can serve as a template or inspiration for building data products with domain-driven design, hexagonal architecture, and spec-driven transformation rules.

Project structure highlights:

.

├── docs/

├── hexagonal_ddd_data_engineering_demo

│ ├── adapters

│ ├── application

│ │ ├── ports

│ │ └── use_cases

│ ├── domain

│ │ ├── data_governance

│ │ └── retail_data_domain

│ └── entrypoints

└── tests

└── ...

Going further: automating Class Generation from Data Contracts

In the examples above, each table and transformation rule is defined explicitly in code. An alternative approach is to use a factory pattern that parses the data contract or other configuration file that can explicit the DAGs and dynamically generates the corresponding classes for each table and data product. This reduces duplication and ensures that updates to the data contract directly propagate to domain behavior.

To implement this, one can define a library of reusable data quality rules and transformation rules. A configuration file, distinct from the data contract, can then map specific rules to tables or flows. A parser interprets this configuration and instantiates the appropriate domain objects, including data sources, data targets, transformation flows, and quality rules.

This approach also empowers business users and product owners to influence data product behavior if it is provided with a user interface to define configuration rules and generate the configuration. You can also imagine using agent capability with a spec-driven approach. I experimented using agents to generate some transformation rules and data quality rules and I was satisfied with the results as agents developers seem to thrive in highly structured projects.

Appendix: let's compare two extremes

For a fast proof of concept, the entire campaign enrichment workflow can be implemented in a single Python script. I call it step 0. This script reads raw campaigns and enriched orders, performs transformations (cleaning channel names, calculating revenue per campaign), validates data quality, and writes the results:

from pyspark.sql import SparkSession

import pyspark.sql.functions as F

# Create Spark session with hardcoded config

spark = SparkSession.builder \

.appName("CampaignEnrichment") \

.config("spark.sql.extensions", "io.delta.sql.DeltaSparkSessionExtension") \

.config("spark.sql.catalog.spark_catalog", "org.apache.spark.sql.delta.catalog.DeltaCatalog") \

.getOrCreate()

# Hardcoded paths

campaigns_path = "/data/bronze/campaigns_raw"

orders_path = "/data/silver/orders_enriched"

output_path = "/data/silver/campaigns_enriched"

# Read data directly

campaigns_df = spark.read.format("delta").load(campaigns_path)

orders_df = spark.read.format("delta").load(orders_path)

# Transform: Clean channel names

campaigns_df = campaigns_df.withColumn(

"channel",

F.lower(F.trim(F.col("channel")))

)

# Transform: Calculate revenue per campaign

campaign_revenue = orders_df \

.groupBy("campaign_id") \

.agg(F.sum("total_amount_eur").alias("campaign_revenue"))

# Join campaigns with revenue

campaigns_enriched = campaigns_df.join(

campaign_revenue,

on="campaign_id",

how="left"

).fillna({"campaign_revenue": 0.0})

# Data quality check: Validate channels

valid_channels = ["email", "sms"]

invalid_count = campaigns_enriched.filter(

~F.col("channel").isin(valid_channels)

).count()

if invalid_count > 0:

print(f"WARNING: Found {invalid_count} rows with invalid channels!")

# Remove invalid rows

campaigns_enriched = campaigns_enriched.filter(

F.col("channel").isin(valid_channels)

)

# Write results

campaigns_enriched.write \

.format("delta") \

.mode("overwrite") \

.save(output_path)

spark.stop()

When Step 0 Makes Sense

This approach is suitable for experimental, fast-moving contexts or initial proofs of concept. It allows teams to deliver value quickly without investing in a full code architecture. However, as soon as the workflow grows, the number of scripts increases, or multiple engineers collaborate, Step 0 becomes a maintenance burden. Refactoring into a more structured architecture becomes necessary to maintain reusability, testability, and governance. When there is a need to rationalize, there is a need for abstraction.

A Practical Perspective

In practice, the choice of code architecture should reflect the team’s ways of working. If the organization lacks clear domain definitions or governance, it may be premature to adopt a complex DDD-style architecture. Conversely, if the workflow is experimental or chaotic, Step 0 can coexist with gradual formalization: define data products, enforce governance, and iterate on the code. Assumptions can be made initially and refined later using continuous refactoring. This iterative approach balances delivering immediate value with building long-term maintainable systems.

Conclusion

I particularly appreciate being able to read the table definitions and transformations of business objects across different maturity levels in a specific code area. By examining the tables, it is straightforward to understand the expected assertions, structure, and constraints of the target tables.

The declarative approach is especially appealing. I can envision reviewing a pull request that updates both the data contract and the corresponding class definitions side by side; this would make code reviews straightforward and transparent. Furthermore each component can be tested in isolation, providing confidence to modify any part of the code to accommodate evolving business requirements or changes in infrastructure. Being able to test robustly was my first motivation to deepdive into this kind of code architecture.

References

- [1] Velappan, V. (2023, 20 octobre). Artificial Intelligence Adoption and Investment Trends in APAC. S&P Global Market Intelligence. S&P Global

- [2] Sanderson, C., Freeman, M., & Schmidt, B. E. (2025). Data Contracts : Developing Production-Grade Pipelines at Scale. O’Reilly Media.

- [3] Deleplanque, V., Hamy F., Lamandé, D., & Mazure, A. (s.d.). RefCard DDD Stratégique: Le Domain-Driven Design stratégique démystifié. OCTO Technology. https://publication.octo.com/fr/telechargement-refcard-ddd-strategique

- [4] wwerner (n.d.). event-storming-cheatsheet: Short cheat sheet for preparing and facilitating event storming workshops. GitHub Repository. https://github.com/wwerner/event-storming-cheatsheet

- [5] Contextive (s. d.). Contextive Documentation. https://docs.contextive.tech/community/guides/setting-up-glossaries/ Contextive

- [6] Alliaume, E., & Roccaserra, S. (2018). Hexagonal Architecture: trois principes et un exemple d’implémentation. OCTO Technology Blog. https://blog.octo.com/hexagonal-architecture-three-principles-and-an-implementation-example

- [7] Adam Wiggins (s. d.). The Twelve-Factor App. 12factor.net. https://12factor.net/config

- [8] Hunt, A., & Thomas, D. (1999). The Pragmatic Programmer. Addison-Wesley.

- [9] Dussaussois, M. (2025). Culture Produit Data: Construire des produits utiles, utilisables, utilisés. OCTO Technology. https://publication.octo.com/culture-produit-data

- [10] Bardiakhosravi (s. d.). agent-context-kit : Context framework for AI coding agents. GitHub. https://github.com/bardiakhosravi/agent-context-kit

- [11] Data Contract (s. d.). DataContract.com. https://datacontract.com/